Trial

Simpson wanted a speedy trial, and the defense and prosecuting attorneys worked around the clock for

several months to prepare their cases. The trial began on January 24, 1995, seven months after the

murders, and was televised by closed-circuit TV camera via Court TV, and in part by other cable and

network news outlets, for 134 days. Judge Lance Ito presided over the trial in the C.S. Foltz Criminal

Courts Building.

The Jury

District Attorney Gil Garcetti elected to file charges in downtown Los Angeles, as opposed to Santa

Monica, in which jurisdiction the crimes took place.[139] The Los Angeles Superior Court then decided to

hold the trial in Downtown Los Angeles instead of Santa Monica due to safety issues at the Santa Monica

Court house owing to the 1994 Northridge earthquake.[140] The decision may have affected the trial's

outcome because it resulted in a jury pool that was less educated, had lower incomes, and contained more

African Americans.[141] Richard Gabriel, a jury consultant for Simpson, wrote that more educated jurors

with higher incomes were more likely to accept the validity of DNA evidence and the argument that

domestic violence is a prelude to murder. Gabriel noted that African Americans were far more likely than

other minorities to be receptive to claims of racially motivated fraud by the police.[139]

In October 1994, Judge Lance Ito started interviewing 304 prospective jurors, each of whom had to fill

out a 75-page questionnaire. On November 3, twelve jurors were seated with twelve alternates. Over the

course of the trial, ten were dismissed for a wide variety of reasons. Only four of the original jurors

remained on the final panel.[142]

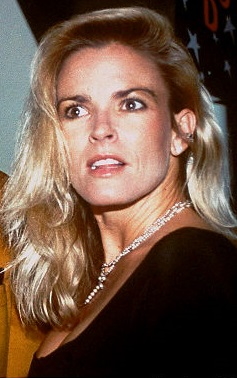

According to media reports, Clark believed women, regardless of race, would sympathize with the domestic

violence aspect of the case and connect with Brown personally. On the other hand, the defense's research

suggested that black women would not be sympathetic to Brown, who was white, because of tensions about

interracial marriages. Both sides accepted a disproportionate number of female jurors. From an original

jury pool of 40 percent white, 28 percent black, 17 percent Hispanic, and 15 percent Asian, the final

jury for the trial had ten women and two men, of whom nine were black, two white, and one

Hispanic.[143][144][clarification needed]

On April 5, 1995, juror Jeanette Harris was dismissed when Judge Ito learned she had failed to disclose

an incident of domestic abuse.[145] Afterwards, Harris gave an interview and accused the deputies of

racism and claimed the jurors were dividing themselves along racial lines. Ito then met with the jurors,

who all denied Harris's allegations of racial tension among themselves. The following day, Ito dismissed

the three deputies anyway, which upset the jurors that did not complain because the dismissal appeared

to lend credence to Harris's allegations, which they all denied.[146] On April 21, thirteen of the

eighteen jurors refused to come to court until they spoke with Ito about it. Ito then ordered them to

court and the 13 protesters responded by wearing all black and refusing to come out to the jury box upon

arrival.[147] The media described this incident as a "Jury Revolt" and the protesters wearing all black

as resembling a "funeral procession".[148][149][150][151]

Prosecution

The two lead prosecutors were Deputy District Attorneys Marcia Clark and William Hodgman, who was

replaced as lead prosecutor by Christopher Darden. Clark was designated as the lead prosecutor

and Darden became Clark's co-counsel. Prosecutors Hank Goldberg and Hodgman, who had

successfully prosecuted high-profile cases in the past, assisted Clark and Darden. Two

prosecutors who were DNA experts, Rockne Harmon and George "Woody" Clarke, were brought in to

present the DNA evidence in the case and were assisted by Prosecutor Lisa Kahn.[152][153][154]

Theory

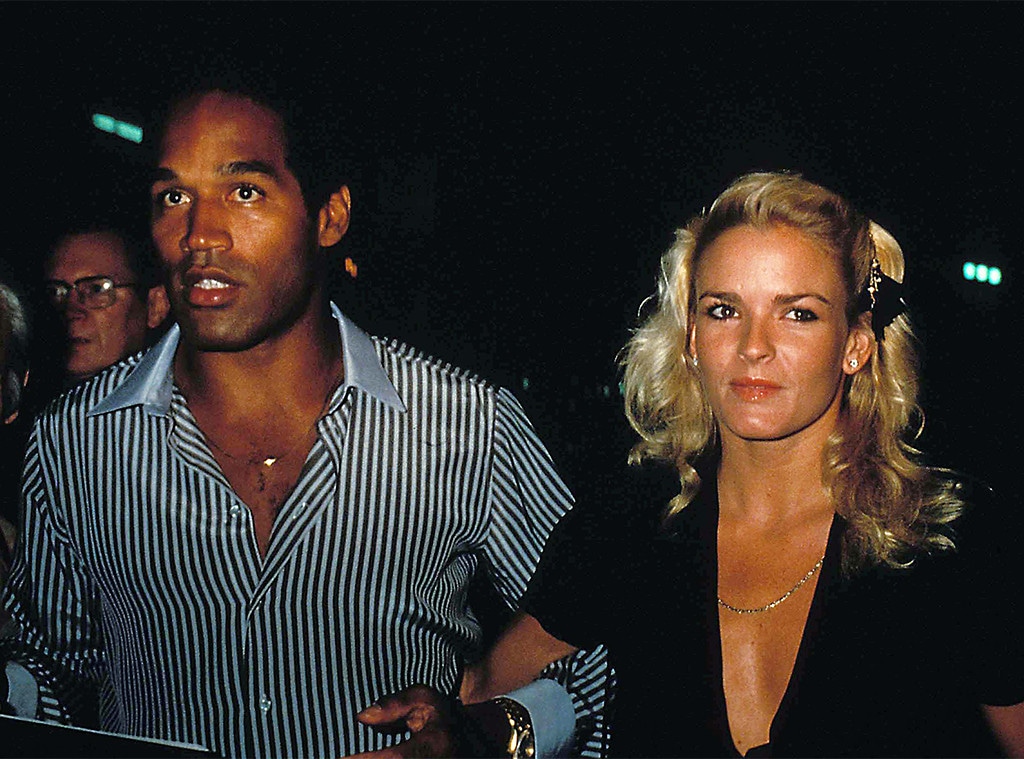

The prosecution argued that the domestic violence within the Simpson-Brown marriage

culminated in

her murder.[155] Simpson's history of abusing Brown resulted in their divorce and his

pleading

guilty to one count of domestic violence in 1989.[156] On the night of the murders, Simpson

attended a dance recital for his daughter and was reportedly angry with Brown because of a

black

dress that she wore, which he said was "tight". Simpson's then girlfriend, Paula Barbieri,

wanted to attend the recital with Simpson but he did not invite her. After the recital,

Simpson

returned home to a voicemail from Barbieri ending their relationship.

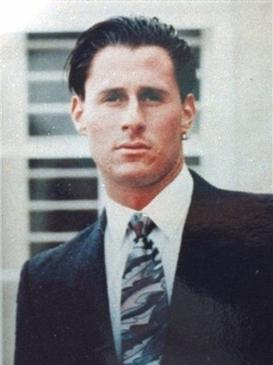

According to the prosecution, Simpson then drove over to Brown's home in his Ford Bronco to

reconcile their relationship as a result and when Brown refused, Simpson killed her in a

"final

act of control". Goldman then came upon the scene to return some eyeglasses and was murdered

as

well in order to silence him and remove any witnesses. Afterwards, the prosecution said that

Simpson walked to his Bronco and drove home, where he parked it and walked into his house.

There, he took off his blood stained clothes, put them in the knapsack (except his socks and

the

glove), put clean ones on, and left towards the limousine. At the Airport, prosecution said

that

Simpson opened the knapsack, removed the clothes, Bruno Magli shoes, and the murder weapon,

and

threw them in the trash before putting the knapsack in one of his suitcases and headed

towards

his flight.[157][158][159]

Timeline

Los Angeles County Chief Medical Examiner Lakshmanan Sathyavagiswaran testified on June

14,

1995,

that Brown's time of death was estimated as between 10:00 pm and 10:30 pm.[183][184]

Kato

Kaelin

testified on March 22, 1995, that he last saw Simpson at 9:36 pm that evening. Simpson

was

not

seen again until 10:54 pm when he answered the intercom at the front door for the

limousine

driver, Allan Park.[185][186] Simpson had no alibi for approximately one hour and 18

minutes

during which time the murders took place.[187] Allan Park testified on March 28 that he

arrived

at Simpson's home at 10:25 pm on the night of the murders and stopped at the Rockingham

entrance: Simpson's Bronco was not there.[188] He then drove over to the Ashford

entrance

and

rang the intercom three times, getting no answer, starting at 10:40pm.[189]

Park's testimony was significant because it explained the location of the glove found at

Simpson's home.[190] The blood trail from the Bronco to the front door was easily

understood

but

the glove was found on the other side of the house. Park said the "shadowy figure"

initially

approached the front door before heading down the southern walkway which leads to where

the

glove was found by Fuhrman. The prosecution believed that Simpson had driven his Bronco

to

and

from Brown's home to commit the murders, saw that Park was there and aborted his attempt

to

enter through the front door and tried to enter through the back instead.[191] He

panicked

and

made the sounds that Kaelin heard when he realized that the security system would not

let

him

enter through the rear entrance.[192] He then discarded the glove, came back and went

through

the front door.[14] During cross examination, Park conceded that he could not identify

the

figure but said he saw that person enter the front door and afterwards Simpson answered

and

said

he was home alone. Park conceded that he did not notice any cuts on Simpson's left hand

but

added "I shook his right hand, not his left".[187]

Back to Top of Prosecution vs Defense

Defense

Simpson hired a team of high-profile defense lawyers, initially led by Robert Shapiro, who was

previously a civil lawyer known for settling, and then subsequently by Johnnie Cochran, who at

that point was known for police brutality and civil rights cases.[228] The team included noted

defense attorney F. Lee Bailey, Robert Kardashian, Harvard appeals lawyer Alan Dershowitz, his

student Robert Blasier, and Dean of Santa Clara University School of Law Gerald Uelmen.

Assisting Cochran were Carl E. Douglas and Shawn Holley. Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld were

also hired; they headed the Innocence Project and specialized in DNA evidence. Simpson's defense

was said to have cost between US$3 million and $6 million; the media dubbed the group of

talented attorneys the Dream Team,[229][230] while the taxpayer cost of prosecution was over

US$9 million.[231]

Theory

The defense team's reasonable doubt theory was summarized as "compromised, contaminated,

corrupted" in opening statements.[232][160] They argued that the DNA evidence against Simpson

was "compromised" by the mishandling of criminalists Dennis Fung and Andrea Mazzola during the

collection phase of evidence gathering, and that 100 percent of the "real killer(s)" DNA had

vanished from the evidence samples.[233] The evidence was then "contaminated" in the LAPD crime

lab by criminalist Collin Yamauchi, and Simpson's DNA from his reference vial was transferred to

all but three exhibits.[234] The remaining three exhibits were planted by the police and thus

"corrupted" by police fraud.[235] The defense also questioned the timeline, claiming the murders

happened around 11:00 pm that night.[236]

Timeline

The physician Robert Huizenga testified on July 14, 1995[237] that Simpson was not physically

capable of carrying out the murders due to chronic arthritis and old football injuries. During

cross-examination, the prosecution produced an exercise video that Simpson made a few weeks

before the murders titled O.J. Simpson Minimum Maintenance: Fitness for Men, which demonstrated

that Simpson was anything but frail.[238] Huizenga admitted afterwards that Simpson could have

committed the murders if he was in "the throes of an adrenaline-rush".[239]

Michael Baden, a forensic pathologist, testified that the murders[240] happened closer to

11:00pm, which is when Simpson has an alibi[241][242] and stated that Brown was still conscious,

standing, and took a step after her throat was cut[243] and that Goldman was standing and

fighting his assailant for ten minutes with a lacerated jugular vein.[244][245]

After the trial, Baden admitted his claim of Goldman's long struggle was inaccurate[246][247] and

that testifying for Simpson was a mistake.[248] Critics claimed that Baden knowingly gave false

testimony in order to collect a $100,000 retainer[249][250][251] because the week before he

testified, John Gerdes admitted[252] that Goldman's blood was in Simpson's Bronco[253] despite

Goldman never having an opportunity within his lifetime to be in the Bronco.[254]

Back to Top of Prosecution vs Defense

The Verdict

Fears grew that race riots, similar to the riots in 1992, would erupt across Los Angeles and the rest of

the country if Simpson were convicted of the murders. As a result, all Los Angeles police officers were

put on 12-hour shifts. The police arranged for more than 100 police officers on horseback to surround

the Los Angeles County courthouse on the day the verdict was announced, in case of rioting by the crowd.

President Bill Clinton was briefed on security measures if rioting were to occur nationwide.

The only testimony that the jury reviewed was that of limo driver Park.[72] At 10:07 am on Tuesday,

October 3, 1995, Simpson was acquitted on both counts of murder. The jury arrived at the verdict by 3:00

pm on October 2, after four hours of deliberation, but it postponed the announcement.[130] After the

verdict was read, juror number nine, 44-year-old Lionel Cryer, gave Simpson a black power raised fist

salute.[340] The New York Times reported that Cryer was a former member of the revolutionary nationalist

Black Panther Party that prosecutors had "inexplicably left on the panel".[341]

An estimated 100 million people worldwide watched or listened to the verdict's announcement.

Long-distance telephone call volume declined by 58 percent, and trading volume on the New York Stock

Exchange decreased by 41 percent. Water usage decreased as people avoided using bathrooms. So much work

stopped that the verdict cost an estimated $480 million in lost productivity.[130][better source needed]

The US Supreme Court received a message on the verdict during oral arguments, with the justices quietly

passing the note to each other while listening to the attorney's presentation. Congressmen canceled

press conferences, with Joe Lieberman telling reporters, "Not only would you not be here, but I wouldn't

be here, either".[342]